Wake Up Dead Man has a killer cast, master plotting and style to spare in a divine murder mystery worth confessing to again and again.

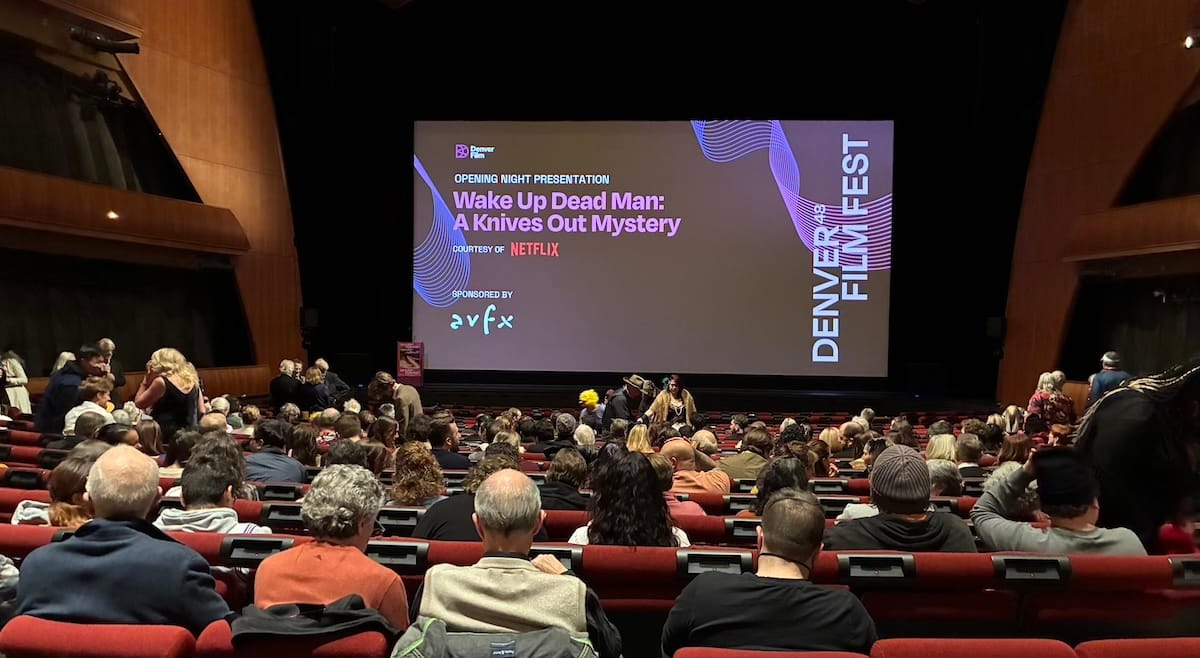

When the lights dimmed at the Ellie Caulkins Opera House on Halloween night, a nearly sold-out Denver crowd was ready for blood, and Benoit Blanc delivered. Wake Up Dead Man: A Knives Out Mystery, the opening night feature of this year’s Denver Film Festival, marks writer-director Rian Johnson’s sharpest and most soulful entry yet in his whodunit series.

Wake Up Dead Man, which is equal parts Gothic morality tale and darkly funny critique of faith and corruption, sees Daniel Craig’s Southern sleuth return to solve another impossible murder, this time in a small-town church that is rotting from within. The result is a funny, politically charged and unexpectedly tender film that solidifies Johnson’s place as one of modern cinema’s best storytellers.

Colorado audiences got an early look at the new ‘Knives Out’ film at the Ellie Caulkins Opera House at the Denver Center Halloween night as part of the Denver Film Festival. | Photo: Toni Tresca

Faith, deceit and a divine crime

After skewering greed and celebrity in Knives Out and Glass Onion, Johnson shifts his lens to organized religion. When the domineering Monsignor Jefferson Wicks (Josh Brolin) collapses mid-sermon on Good Friday, his death seems both miraculous and monstrous. Suspicion immediately falls on the parish’s newest arrival: the idealistic but volatile Reverend Jud Duplenticy (Josh O’Connor), a former boxer-turned-priest with a violent past.

Enter Benoit Blanc, whom Craig portrays with a honeyed Southern draw thick enough to cut glass and a swaggering confidence in his own ability to solve the complex crime. Summoned by the overwhelmed local police chief (Mila Kunis), Blanc finds himself unraveling an impossible murder where faith and fanaticism blur into one.

What begins as a straightforward stabbing soon expands into a layered puzzle involving long-buried family secrets, a missing inheritance and a congregation bound by both devotion and deceit. Johnson’s script is his most classically structured mystery to date, steeped in the locked-room tradition of John Dickson Carr’s The Hollow Man. For nearly 45 minutes, Blanc doesn’t appear, allowing viewers to soak in the poisonous atmosphere of the church and its congregation.

When Blanc finally steps in, the tone shifts seamlessly from psychological drama to procedural puzzle box, complete with locked-room trickery and theological riddles. And, as is always true in the best murder mysteries, every revelation recontextualizes the last.

A flock of sinners and saints

O’Connor gives the film its bruised, beating heart as Reverend Jud, a man desperate to reconcile his faith with his fury. His haunted eyes and hesitant gestures make him as tragic as he is suspicious, embodying the film’s central question: What do we cling to when belief fails us?

One of the film’s finest scenes crystallizes that question with startling gentleness. While chasing a lead, Jud and Blanc phone Louise (Bridget Everett), an employee at a company that handles grave openings, to learn who called on Wednesday to open the church’s tomb ahead of the Friday murder. The scene begins as a comedic moment, with Louise rambling as Jud tries and fails to redirect her attention back to the point, until she admits she is reeling from a brutal argument with her mother, who is now in hospice.

Afraid their last words will be their worst, Louise breaks down. Jud quietly leaves Blanc, closes the door and ministers to her over the phone in the other room. Johnson lingers on the stillness. It’s a tender, human detour that shows the church at its best: not as a cudgel, but as care. Despite the fact that the mystery is still ongoing, the ministry continues.

Craig continues to reinvent Benoit Blanc in fascinating ways. Gone is the breezy omniscience of Glass Onion; this Blanc is more uncertain, even humbled. Watching him struggle to make sense of the community’s contradictions gives the film real emotional weight. His sparring sessions with O’Connor crackle with mutual curiosity and moral tension.

Brolin, meanwhile, gives a towering performance as the self-styled holy man whose sermons drip with manipulation. His Monsignor Wicks is a pulpit bully whose charisma barely hides his cruelty. It’s an audaciously physical turn, full of snarling gestures and cold control.

Glenn Close matches him beat for beat as Martha Delacroix, the church’s self-proclaimed matriarch in charge of all behind-the-scenes operations. Close imbues every line with coiled devotion, making her both fearsome and pitiable. Close’s Martha is a believer so loyal she’s lost sight of what she’s worshipping.

Around them, the supporting players who make up the congregation sketch out a whole moral ecosystem. Kerry Washington’s closed-off, high-strung attorney, Vera Draven; Daryl McCormack’s power-hungry right-wing influencer, Cy Draven; and Cailee Spaeny’s disabled, faith-seeking former cellist, Simone Vivane, all reveal different aspects of spiritual desperation.

Even smaller roles, like Jeremy Renner’s drunken doctor, Dr. Nat Sharp, or Thomas Haden Church’s newly sober groundskeeper, Samson Holt, feel fully lived in. Every actor appears to understand Johnson’s tonal high-wire act, which balances sincerity and satire without ever losing emotional ground.

And yes, it’s funny — often uproariously so. Johnson peppers the script with sardonic one-liners (“I was young, dumb and full of Jesus,” O’Connor deadpans early on) that break the tension without deflating it.

The gospel according to Rian

Technically, Wake Up Dead Man is Johnson’s richest film to date. Cinematographer Steve Yedlin transforms the upstate New York setting into a chiaroscuro cathedral of doubt, with sunlight streaming in through the window and shadows stretching like guilt across the floor. The composition is expansive, with wide shots that emphasize how small and fallible these people look inside the grandeur of their faith.

Nathan Johnson’s score trades the bombastic orchestration of Knives Out for something more meditative, including strings that hum with doubt and organs that echo with unease. The sound design complements this shift: bells toll faintly in the distance, pews creak like old bones and the foliage crunches violently as characters traverse the town’s rural environment. The result is a film that sounds as haunted as it looks.

Editor Bob Ducsay’s rhythm is patient but purposeful. The first act’s slow burn gives way to a breathless second-half investigation and a finale that dares to pause rather than explode. Some may find its tempo languid compared to the first two films’ breezy pace, but its restraint pays off in spades.

The climactic revelation, accompanied by a shaft of light breaking through the church’s stained glass, feels more like a revelation than a twist. Without spoiling anything, Johnson refuses to let Blanc deliver his traditional grandstanding monologue. Instead, the detective steps aside, yielding the floor to faith itself. It’s a quietly radical move in a genre built on certainty, turning the conclusion into something as spiritual as it is satisfying.

At once a riveting mystery, a biting satire of religious hypocrisy and an unexpectedly moving meditation on belief, Wake Up Dead Man proves there’s still plenty of life left in Johnson’s murder-mystery franchise. It’s the rare blockbuster that dares to question not only who committed the crime, but why we seek answers at all.

Catch it on the big screen if you can before it hits Netflix on December 12. The grandeur of the church setting and the collective joy of discovery deserve to be experienced communally. In a film landscape rife with hollow puzzles, Johnson reminds us that a mystery can still have soul.

A Colorado-based arts reporter originally from Mineola, Texas, who writes about the changing world of theater and culture, with a focus on the financial realities of art production, emerging forms and arts leadership. He’s the Managing Editor of Bucket List Community Cafe, a contributor to Denver Westword and Estes Valley Voice, resident storyteller for the Bonfils-Stanton Foundation and co-host of the OnStage Colorado Podcast. He holds an MBA and an MA in Theatre & Performance Studies from CU Boulder, and his reporting and reviews combine business and artistic expertise.

Leave A Comment