Reviews of The Righteous, Der Rosenkavalier and L’elisir d’amore

Originally posted on SharpsandFlatirons.com

The Santa Fe Opera premiere of The Righteous, a new opera by Gregory Spears to a libretto by Tracy K. Smith that I saw Aug. 7, offered some memorable singing, a skillful and expressive orchestral score, fine direction by Kevin Newbury, flexible set designs by Mimi Lien, and intermittent drama.

The plot is a tale of faith, betrayal and torn loyalties that shatter relationships and create family conflicts. The central character is David, a charismatic preacher widely known for his compassion. Surrounding him are his childhood friend Jonathan, a struggling gay man; Jonathan’s father Paul and sister Michele; David’s friend Sheila and her husband Eli. (If you are seeing Biblical implications in the names, that is entirely intentional.)

The situation offers possibilities for strong emotions, as David betrays his first wife (Michele) and breaks up another marriage pursuing an affair with Sheila, then gives up the ministry for a compromising career in politics. Along the way he turns his back on Jonathan, who is portrayed as a gay man lost in the treacherous waters of the 1980s AIDS crisis.

Unfortunately, the opera does little more than skate on the surface of these opportunities. The obvious issues of the time are touched — gay rights, women, AIDS, the war on drugs, racial justice, youth culture — but thrown up as tokens without depth or nuance. The opera boils down to a family drama, with faith and politics serving as context.

The potential emotional depths are sounded periodically in arias from the first act, where most of the action plays out. The second act turns into dry conversations about ’80s politics. Both Michele and Sheila, David’s first and second wives, have arias exposing their feelings, but only at the very end do we get insight into David’s feelings. After Jonathan walks away from him to move to California, David questions how his choices have ruined his relationship with Jonathan, whom he loves deeply if platonically, and wonders if he has betrayed his principles.

In a stirring final scene with chorus, David asks God “What did I mistake for you?” and concludes “Life is long and wisdom slow.” This truism is certainly suggested by David’s trajectory, and the final chorus is stirring, building to some of the most impactful music of the opera. But a powerful ending does not redeem the dramatically stagnant scenes before it.

Spears writes effectively for orchestra, and it is the orchestral music that defines the opera’s progress. The setting and mood for each scene are established in the orchestra, which sets moods and outlines the action. But the vocal parts fall into an unfortunate pattern in contemporary opera: musical declamation of the text with wide leaps defining emotional high points, but little to remember. Both Michele and Sheila have emotive arias in the first act that delineate their respective dilemmas, but they are scarcely distinguishable one from the other.

Of a generally strong cast, Michael Mayes was a standout as David. Both vocally and dramatically the center of every scene where he appears, he was thoroughly believable as a charismatic leader who would be tapped for political office. He had strength to spare all the way to the final choral apotheosis, his and Spears’s strongest moment, his confessional musings cutting through the powerful Santa Fe Opera chorus.

As Jonathan, the countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo handled the wandering lines and leaps of his part cleanly and eloquently. His early portrayal of an angry post-adolescent was spot on, but I did not see him mature over the course of the opera, which spans 11 years. And I have to ask: Is it succumbing to stereotypes to cast the gay man as a countertenor, who will always sound younger and more feminine than the other characters?

The leading women were all first-rate. As Sheila, Elena Villalón sang her first act profession of faith, “If I were a man of God,” with as much expression as the declamatory setting allowed. She handled the wide range of her part well, hitting all the leaps with accuracy and soaring smoothly into her highest rage. Jennifer Johnson Cano was a sympathetic Michele who sang with great conviction in her emotional confrontation with her husband. The rest of her part has little musical interest, but she did all that could be expected of a character who exists only to be betrayed and has no other defined qualities.

Greer Grimsley portrays Paul, Jonathan’s and Michele’s father and the governor of a “Southwestern state” dependent on the oil economy (more Texas than New Mexico), as a conventional politician, full of self-assurance and certainty of belief. Beyond swagger and a cowboy hat, there is little evidence of his personality.

As Paul’s wife Marilyn, Wendy Bryn Harmer was vocally solid. She created the perfect political wife, totally composed — big hair and all; it is the 1980s — in charge behind the scenes and basking in her husband’s success. Brenton Ryan was thoroughly real as the political consultant CM, always at the governor’s side and never at a loss.

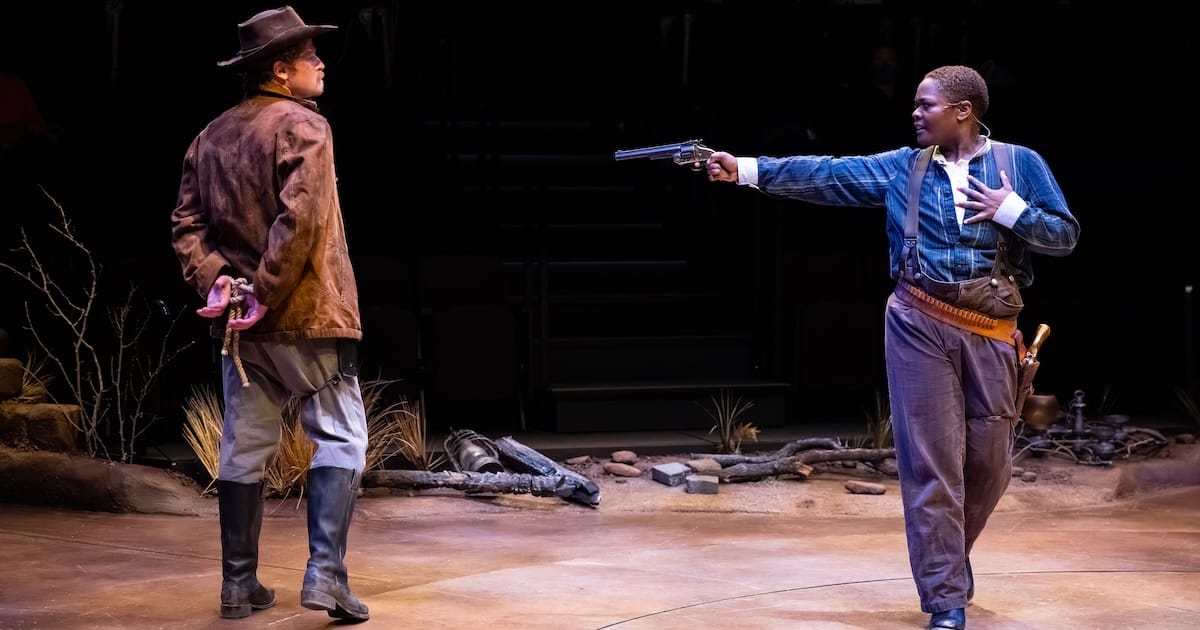

In the role of Jacob, minister of a black church in a poorer —i.e., segregated — part of town, Nicholas Newton sang with power and conviction as he confronted David, by the second act a governor who on political grounds now wants to punish the poor and the black for the crack epidemic.

Jazmine Saunders and Natasha Isabella Gesto were perfectly in character as Sheila’s daughter and college friend, Shannon and Deirdre, young women of conviction who are facing an uncertain future in a turbulent time. Andrew Turner has little to do as Eli, Sheila’s abandoned husband who spends most of the opera on military deployment. The little he has he did with serious demeanor and commitment.

Lien’s set moved easily from one location to another with rotating side panels and a few movable pieces clearly defining each space. Kevin Newbury’s direction helped illuminate relationships and contexts. Demario Simmons’s costumes were faithful to a time period that I for one can recall, portraying the free-wheeling youth culture as well as the uptight political world. De Souza managed the orchestra with sensitivity and careful attention to the score, finding the right balance and style as scene followed scene.

The Righteous offers some powerful musical moments that punctuate a halting drama, especially in the women’s Act I arias and the final choral scene. These moments are moving and musically effective, but the drama does not live up to their impact.

Rachel Willis-Sørensen (Marschallin) and Paula Murrihy (Octavian). Photo by Curtis Brown.

Der Rosenkavalier

Santa Fe’s Der Rosenkavalier is a shared production with Garsington Opera and Irish National Opera. It is visually striking, sometimes beautiful, but the last scene is so elaborate it took a 35-minute intermission to set it up, so that the performance ended after midnight (Aug. 8–9).

The direction by Bruno Ravella shied away from neither the erotic content of the opera, nor the humor. At times this was welcome, since we are not as prudish today as in 1911, when Richard Strauss’ most loved opera was first performed. (Some early productions were forbidden to have a bed onstage in the first act.) And it is described as a comic opera.

But any performance requires a careful balancing act, because the opera also includes serious topics including aging, the treatment of women by men, the true meaning of love and the different meanings of nobility. The production leans too far in the comic direction. As an audience member whom I overheard said, “They could have done ten percent less.”

For example, consider Fanninal, the nouveau riche father of Sophie, the ingenue who captures Octavian’s heart. Like many new arrivals in the moneyed class, he is a little bit ridiculous. But Ravella directs him as a buffoon. This gets some easy laughs in the Second Act, when Sophie’s fiancé, the boorish Baron Ochs, arrives to claim his bride. But going too far in this direction undermines the role Fanninal plays in the deeply emotional final scenes.

The entire Third Act has to be handled carefully. If the burlequeries designed to entrap Ochs and free Sophie from her disastrous engagement are too ridiculous, the audience will laugh (as they did here), but the transition to the profound sentiments of the final trio becomes difficult. There is plenty of fun to be had without a stage full of visibly “pregnant” women, an over-the-top musical band with a Simon Rattle look-alike conductor, and similar excesses. As much as I enjoyed the performance, a lighter touch here — “ten percent less” — would have been better.

The action for this production has been transferred to the 1950s, with the younger characters — mostly Sophie, since Octavian is usually in uniform — dressed for the ’60s. The ’50s dress works well, excepting only the Marchallin’s overdone white-and-silver ensemble in the final act. Sophie’s outfits perfectly captured the innocent teen of a wealthy ’50s family. (Disclosure: I knew girls like that.)

But this updating has one big problem: 1950s Vienna was nothing like the 1740s Vienna of Strauss’ opera. All of Europe had been devastated by World War II; palaces were destroyed and life was hard. No one in postwar Vienna had swarms of liveried servants, as in the Marschallin’s and Fanninal’s homes. Altogether, the production portrays a style of life that never returned.

Further, the class divisions between nobility and the common people were not as strict as in the 18th century. Marriage regulations, a minor point in the plot, would have been unlike those of the 1740s. This destroys any credibility of the 1950s setting.

There are intentional mistranslations in the seat-back titles, designed to fit with the later period—a common occurrence with updated productions. In the libretto, the Marschallin invites Octavian to ride alongside her carriage in the Prater; the titles said that they could walk together. On the other hand, the Marchallin’s proto-feminist inclinations, when she tells Octavian “Don’t be like other men,” or “I’m starting to dislike all men,” fit better in the 20th century than the era of Empress Maria Theresa.

In the critical role of the Marschallin, Rachel Willis-Sørensen gave a memorable performance. She was able to sustain her luscious lines at the softest volume and sing at full volume without losing control. Her posture standing still at the end of her Act I monologue conveyed more than any affected pose. If she had less impact in the final act, that is because of the madness right before her entrance, and her frankly awkward gown.

In her movements and stances, Paula Murrihy looked the part of the 17-year-old boy Octavian as well as anyone I have seen. Her voice was a little too lush and womanly to convince entirely, especially in the louder passages when her vibrato spread uncomfortably. Pitch placement was careful throughout, and the softer passages flowed smoothly. Her scenes with the Marschallin and with Sophie made the shock of discovering a girl his own age meaningful and deeply moving. I confess; I cannot see the final scene without getting a little misty, and I did here.

Ying Fang was a delightful Sophie, moving with either girlish glee or the hesitant fragility of an adolescent trying to make her way in an adult world. Her facial expressions as she exchanged glances with Octavian would capture anyone’s heart, while her voice soared beautifully into the highest registers in their duets, always the touchstones of any Rosenkavalier performance. Musically and theatrically, she became the very essence of a convent girl on the threshold of adulthood.

Matthew Rose thoroughly embraced the comic aspects of Baron Ochs, just as his garish costumes captured the bad taste of the formerly rich provincial. He blazed though Ochs’s dense text in Act I capably, his sturdy bass always solid, even to the lowest notes that are the main obstacle of the role. Ochs must be fun for any bass, as it seemed to be for Rose.

Within the limits imposed by the direction, Zachary Nelson filled the role of Fanninal admirably. Perfectly foolish in Act II, he was more dignified and human in the final act. The Italian tenor of David Portillo soared easily through his one aria, cutting through all the distracting craziness at the Marchallin’s levee (did they have those in the ‘50s?). Bernard Siegel and Megan Marino brought the scheming Valzacchi and Annina to life, making them the slippery characters they are supposed to be (and their types exist in every era).

The ultimate foundation of any performance of Rosenkavalier is the orchestra. Conductor Karina Cannelakis led a beautiful, expressive performance, showing a deep appreciation and understanding of Strauss’ late Romantic score, pulling out all the emotion that the orchestra can project. The orchestra responded with an idiomatic Romantic sound and performance, soaring strings, resounding brass and skittering woodwinds as required.

Yes, it ended late, but it was worth it for the transformative uplift of the end. And the last word goes, as it does in the opera, to a child, here played by Maximilian Moore. A welcome delight as Cupid, he was a worthy replacement for the original racist trope of the Marschallin’s servant. No dropped handkerchiefs here, just a sprite popping from the floor to wave a rose as Strauss’ music skips happily to its close.

Luke Sutliff (Sgt. Belcore) in Donizetti’s L’elisir d’amore | Photo by Curtis Brown.

L’elisir d’amore

Donizetti’s L’elisir d’amore (The elixir of love), coming after four operas with serious moments and strong emotions, was the perfect comic finale for the season (seen Aug. 9).

The production is full of raucous comedy that fits the spirit of the original. Here the only serious thought is the message not to run away from your true feelings. This moral is conveyed through ridiculous situations and one-dimensional, but strikingly funny, characters. It is a fun, colorful production, in keeping with both the buoyant spirit of Italian comic opera and the period selected for the production, Italy after World War II. Nemorino’s bright red sports car provided several especially funny moments. Sergeant Belcore and the soldiers drove in on a jeep. A priest entered on a motor scooter.

While the period provided good comedy and never got in the way of the fun, it created one huge logical hole that has to be ignored as it cannot be reconciled. A turning point in the opera comes when Nemorino, desperate to buy the wine he thinks is Isolde’s love potion, enlists in Belcore’s regiment for the bonus he will receive.

But, as shown in the production, Italy after the war was occupied by the U.S Army. Belcore is an American soldier. And no Italian peasant could have enlisted in the American Army. In case you miss this giant hole in the plot, Belcore displays an Uncle Sam recruitment poster. So what seems at first a clever and amusing updating turns out to be impossibly anachronistic.

To be fair, the audience laughed throughout, either unaware of, or happy to ignore, the illogic at the core of the plot. Do stage directors — in this case the otherwise successful Stephen Lawless— not think about such issues? Or do they expect the audience not to care?

From the beginning Jonah Hoskins sang with an emotive tenor, his smooth, Italianate style only marred by a tight, nasal sound when pushed. His “Una furtive lagrima” was sung with sincerity of feeling and was rewarded with cheers.

Yarita Véliz was a first-rate Adina, singing with a bright sound and gleaming coloratura. She floated buoyantly through her arias with no sign of strain. In a nuanced performance, her attraction to Nemorino was hinted throughout, making their apparent alienation all the more poignant, and the final reconciliation (including a quick, laugh-inducing make-out session in the sports car) more credible and satisfying.

Luke Sutliff shone as a bragging and swaggering Belcore, with a resounding voice and cocky manner. You cannot be surprised at the end when this lusty sergeant happily surrenders Adina, because “the world is full of women.”

In the role of “Doctor” Dulcamara, Alfredo Daza, earlier the stern Giorgio Germont in La Traviata, was here an artful snake oil salesman, always with an eye on the main chance. Daza has the booming baritone that Dulcamara needs as he hawks his quack miracle cure to the credulous villagers. Caddie J. Bryan was charming as she played the awkward Gianetta with comic zest.

In his stage direction, Lawless found many original comic touches without resorting to formulaic slapstick or tired shtick. Conductor Roberto Kalb kept the performance moving ahead with great energy and zest. The Santa Fe Opera chorus was as usual terrific.

Peter Alexander holds a Ph.D. in musicology from Indiana University. He is retired from the University of Iowa, where he was director of media relations for all the arts organizations on campus for 23 years. Since his retirement he has written for Boulder Weekly, and currently writes news stories and reviews of classical music for his blog, Sharpsandflatirons.com. He is also principal clarinet for the Longmont Concert Band, and worked for many years as a church choir director.

Leave A Comment