Despite a stellar cast and lofty ambitions, Joachim Trier’s latest outing, Sentimental Value, is a cold, slow exercise in self-importance.

Joachim Trier’s Sentimental Value had a lot of buzz when it arrived in Denver this weekend. It had already premiered to rapturous reviews at the Cannes Film Festival in May, where it won the Grand Prix, and the presenter who spoke before the screening at the Denver Botanic Gardens on November 2 as part of the 48th Denver Film Festival described it as his favorite film of the year.

But as the credits rolled, the room felt deflated. What Trier and longtime collaborator Eskil Vogt have created is not a revelation but a cold, weepy European drama with nothing new or particularly interesting to say.

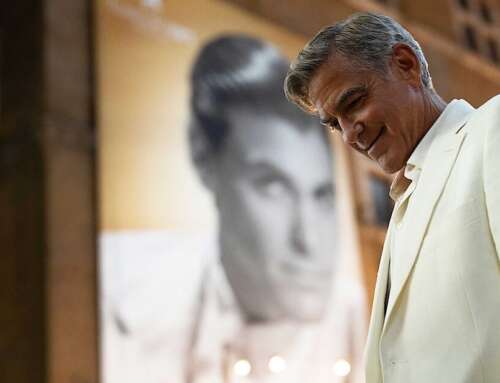

The Norwegian film follows two sisters, Nora (Renate Reinsve), a tense stage actress, and Agnes (Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas), a mother with a stable home life and steady job, who reunite after the death of their mother to confront their father, Gustav (Stellan Skarsgård), a once-famous film director who abandoned them years ago.

Gustav, now desperate for a comeback, announces he’s making a deeply personal film about his mother’s suicide in the family’s Norwegian home. He offers the lead role to Nora, but she refuses, forcing him to cast an American actress, Rachel Kemp (Elle Fanning), instead.

There’s an outline here for a rich, thorny exploration of how art can both expose and obscure personal truth. But Trier’s approach is so austere, so bloodless, that it never finds an emotional core. Every interaction feels muted and self-conscious, as if the characters were performing grief rather than feeling it.

Chillier than Norway in November

Reinsve’s performance as Nora feels frustratingly opaque. The character’s anxiety about performing and her simmering resentment toward her father never register as real emotions so much as familiar gestures, repeated without variation. She spends most of the film locked in icy restraint, moving briskly through scenes without ever revealing what drives her or how she truly feels.

Agnes, played by Lilleaas, is fine in the role but remains frustratingly in the background. She spends most of the film looking flustered, reacting rather than acting, and her motivations, especially when it comes to her father or her shifting feelings about his film, never fully make sense. Trier seems unsure what to do with her beyond using her as a contrast to Nora, leaving the character underdeveloped and emotionally adrift.

Skarsgård’s Gustav, meanwhile, is a void at the center. We’re told he’s a larger-than-life figure who’s brilliant, difficult and yet strangely seductive, but Trier never shows us that man. Skarsgård underplays the role, and his emotional distance drains the film of urgency. He’s neither monstrous nor magnetic, just vaguely sad and self-involved.

The only spark of life comes from Fanning’s Rachel, whose storyline briefly jolts the film awake. As a Hollywood star swept up in the promise of working on high art, she brings a wry awareness that cuts through the fog of Norwegian melancholy. Watching her struggle to meet Gustav’s lofty, undefined expectations — such as speaking English in a film meant to be Norwegian, trying to access emotions that don’t belong to her and being asked to dye her hair to look more like Nora — offers the film’s one glimpse of self-awareness.

When Rachel ultimately admits she can’t do the role without compromising his vision, it’s the rare scene that feels honest and alive. In that exchange, we glimpse what Sentimental Value might have been: a nuanced study of creative vulnerability.

But that spark quickly fades. The movie sinks back into its habitual coolness, smothered by static pacing and inert editing. Scenes end abruptly with hard cuts to black, as if the film itself keeps losing interest in its own conversations. This stop-start rhythm destroys any sense of momentum and makes the experience feel interminable.

Even the film’s most visually ambitious moments, like a bizarre montage layering the faces of Gustav and his daughters, land as empty affectation. Instead of building meaning, Trier’s style announces it, straining for profundity that never arrives.

Kasper Tuxen’s cinematography captures the sterile beauty of winter interiors, and Hania Rani’s score tries valiantly to fill the emotional void with a sparse score that effectively accents the scenes, but no amount of craft can hide the flatness beneath or excuse how long it takes to communicate its trite themes.

The pacing is the film’s real undoing. Sentimental Value moves with such glacial deliberation that even its most charged confrontations feel drained of urgency. Scenes stretch on long past their emotional peak, filled with lingering silences and slow, heavy exchanges that often don’t build to anything. There’s no momentum or release, just a steady rhythm of brooding and retreat.

Art about art, without insight

By the end, Gustav’s self-mythologizing is rewarded. His daughters read his script, declare it brilliant and line up to help him make his latest masterpiece, as if decades of absence and resentment can be undone by a few pretty pages. Trier clearly believes in the redemptive power of cinema, but he never earns that redemption here.

The final act skips straight from revelation to resolution, cutting from Nora’s sudden change of heart to a film set bathed in forgiving light, as though the act of creation itself absolves everyone involved. What’s meant to play as catharsis lands as pure self-congratulation, a closing argument for art’s importance that feels airless and insular.

It’s hard not to see Sentimental Value as a film about privileged artists mistaking their own wounds for depth. Trier and Eskil Vogt have explored this terrain before with humor and genuine insight, but here the self-reflection calcifies into self-importance. The film wants to say something universal about legacy and forgiveness, but it can’t see beyond its own reflection.

By the time the credits roll, what lingers isn’t empathy or revelation but exhaustion. Sentimental Value mistakes seriousness for substance, draping a thin story in prestige aesthetics and calling it art. Trier remains an intelligent filmmaker, but this is a rare misfire. For a film so obsessed with what we leave behind, it leaves little of value at all.

A Colorado-based arts reporter originally from Mineola, Texas, who writes about the evolving world of theater and culture—with a focus on the financial realities of making art, emerging forms and leadership in the arts. He’s the Managing Editor of Bucket List Community Cafe, a contributor to Boulder Weekly, Denver Westword and co-host of the OnStage Colorado Podcast. He holds an MBA and an MA in Theatre & Performance Studies from CU Boulder, and his reporting and reviews combine business and artistic expertise.

Leave A Comment