Clint Bentley’s adaptation of Denis Johnson’s novella, Train Dreams, depicts a logger’s lonely life through Joel Edgerton’s understated, soulful performance.

Set in the early 20th-century Pacific Northwest, Train Dreams is a quiet epic of grief and industry, anchored by Joel Edgerton’s lived-in turn and Clint Bentley’s unflinching direction. The film plays out like a memory, quietly following one man’s lifelong struggle to find meaning as the railway and modernity cut through the wilderness that once defined him.

I saw Train Dreams on Nov. 2 at the Holiday Theater during the 48th Denver Film Festival, where Bentley sent a pre-screened video thanking us for attending the screening and admitting how punishing the on-location Washington shoot was. That authenticity is embedded in every frame of Train Dreams, Greg Kwedar and Bentley’s adaptation of Denis Johnson’s 2011 novella, a film that is both beautiful and punishing.

The story follows Robert Grainier, played with quiet force by Joel Edgerton, a logger helping carve the railroad through the Pacific Northwest. The work consumes him, keeping him far from home as industry reshapes the wilderness around him.

He falls in love with Gladys, played by Felicity Jones, builds a cabin and starts a family, only to lose everything when a wildfire devours their world. What remains is a man hollowed out by grief, stumbling through decades of solitude and survival, never certain what he’s still living for.

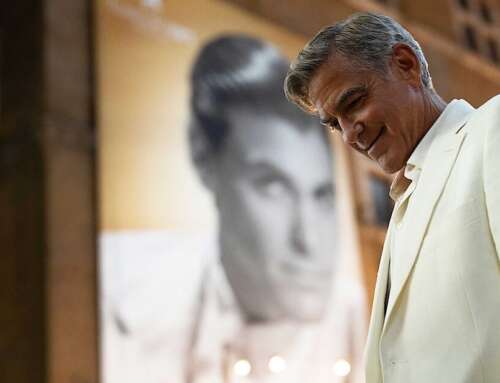

Joel Edgerton with Felicity Jones in ‘Train Dreams.’ | Image: Netflix

Intimate acting

Edgerton’s performance anchors the film with remarkable restraint. His Robert is a man shaped by hard labor, isolation and loss, and while he’s stoic, he’s not unfeeling. Edgerton communicates more with the set of his jaw and the weight of his gait than with dialogue, and it’s riveting. When emotion breaks through, it feels earned.

Jones brings warmth and spark to her brief but indelible scenes as Gladys. Jones and Edgerton have a natural chemistry together that makes the later devastation unbearable. Later, Kerry Condon’s Claire, a forestry worker who shares a brief, soulful connection with Grainier, adds quiet depth, showing how grief can bind strangers.

The supporting cast sharpens the film’s moral edges. William H. Macy’s Arn Peeples, a world-weary explosives expert, voices doubt about their endless cutting of the forest. His musings about trees fighting back hint at an early environmental awareness that hangs over the story like mist. Nathaniel Arcand’s Ignatius Jack, a shopkeeper and friend to Robert, offers moments of kindness that tether Robert to life after tragedy.

Picturesque environment, brutal world

Bentley’s direction is patient and confident, working in concert with Adolpho Veloso’s cinematography. The camera lingers on landscapes that dwarf the men within them. A shot following a tree’s fall from trunk to earth captures the sheer violence of their labor. At times, those long takes feel like mercy; at others, they trap us in harsh circumstances.

When it refuses to cut during horror, such as a racist assault Robert witnesses on the rail line or him dealing with the aftermath of the wildfire, the long takes become almost punitive, forcing us to sit in the moment as life refuses to offer a clean exit. That blunt honesty extends to the logging sequences, where the work reads as both choreography and war.

Parker Laramie’s editing trusts the audience’s attention, letting scenes breathe without dragging. The film’s 102 minutes move with deliberate rhythm, spacious yet tightly composed. Bryce Dessner’s score, with its mournful strings and delicate piano, blends into the natural sounds of saws, wind and fire until music and environment are indistinguishable.

Despite its somber tone, there’s quiet humor and human texture amid the grief. A small, funny exchange about a chicken; a scruffy dog that tethers Robert to the living; the rhythms of his later gig driving a horse-and-buggy around town like a pre-rideshare courier. These fleeting sparks of warmth remind us that even in a world defined by hardship, meaning comes from endurance and the fragile beauty of ordinary moments.

Train Dreams is not flashy and never pleads for attention. Bentley and Kwedar create an adaptation that preserves Denis Johnson’s spare lyricism while expanding it into a cinematic language.

Edgerton, who should be in awards contention, delivers one of his finest performances, carrying the film’s emotional weight with the quiet dignity of a man who has seen too much and says too little. His performance refuses easy catharsis, trusting the audience to sit with the silence, to feel the ache of time and the small mercies that persist in its wake.

Train Dreams is a profound meditation on what it means to keep moving even when the world no longer resembles the one you built your life around. I left the screening shaken but strangely at peace, as its final images rustled in my mind like wind through the canopy.

A Colorado-based arts reporter originally from Mineola, Texas, who writes about the evolving world of theater and culture—with a focus on the financial realities of making art, emerging forms and leadership in the arts. He’s the Managing Editor of Bucket List Community Cafe, a contributor to Boulder Weekly, Denver Westword and co-host of the OnStage Colorado Podcast. He holds an MBA and an MA in Theatre & Performance Studies from CU Boulder, and his reporting and reviews combine business and artistic expertise.

Leave A Comment