La Traviata soars while Don Giovanni is less successful

Originally posted on SharpsandFlatirons.com

Opera productions seem to go through trends. That was certainly the case at the Santa Fe Opera this summer: Of the five productions, only one — the world premiere of The Righteous by Gregory Spears, set in the 1980s — remained in the time period for which it was conceived. The other four — La Traviata, Don Giovani, Der Rosenkavalier and L’elisir d’amore — were shifted forward to more recent times.

Proving that time shifts can work in the right circumstances, some of the productions worked very well in their updated periods. Others were less successful.

La Traviata

Verdi’s La Traviata, updated to 1930s Paris, is a glittering success in almost every way. Armenian soprano Mané Galoyan is as good a Violetta as I have seen. As Alfredo, Uzbekistan tenor Bekhzod Davronov matches her vocally very well. Stand-in Alfredo Daza, the Mexican baritone rounding out the international cast, is a powerful, if blustery, Giorgio Germont.

Conductor Corrado Rovaris brought out the Italianate nuances of the score without ever overpowering the singers. The performance I head (Aug. 5) was filled with glorious, touching pianissimo singing, especially from Galoyan, and every word, every note was clearly heard no matter how softly. Luisa Muller’s direction created a human drama where many productions are satisfied with conventional routine.

The set by Christopher Oram places evocative spaces on a turntable. The Parisian interiors are elaborately decorated in silver, with discrete lighting adding a touch of color. The rotating set is used strategically: In the first act, Violetta’s public scenes at the party are placed in an ornate salon, while her private moments and scenes with Alfredo move smoothly to an interior bedroom. It’s a contrast that sets up the following scenes with the public alternating with the private. The lovers’ country retreat is appropriately rustic, neither too grand nor too shabby. The sets and costumes adhere carefully to the 1930s aesthetic.

An outrageous party

A special word for Act II Scene 2, at Flora’s party: Decorated in bright reds, it is a satanic costume party, with characters in various outrageous costumes. Intentionally over the top, the scene evokes every American conception of the Paris of Hemingway, Pound and les années folles (the crazy years) when the arts flourished despite a worldwide depression. After the restrained colors of the previous scenes, this hits like a blow to the face, creating exactly the shock that Violetta’s return to her life of decadence implies.

For all the strengths of the production, it is Galoyan’s Violetta that makes the greatest impact. Her bright, focused voice suits the role ideally. Her acting was on a par with her emotive singing, ranging from piercing moments of fury to heartrending fragility. Her delicate pianissimos carried easily and never lost nuance or flattened out to expressionless undertones. Her most affecting moments were in the second and third acts, when she is overcome by the tragic fate that she can see coming. At the end, her frailty was made tragically real in her singing.

In her director’s notes, Muller describes Traviata as a memory play, with the coming (or remembered) events suggested in tableaux during the Prelude. Violetta, she writes, is “a woman in command of her life choices” who “knows that the end of her life is approaching.” Both the staging and Galoyan’s performance reinforce that conception, making Violetta the emotional center of the opera. The life of a 19th-century courtesan seems remote today, but this is a Violetta current audiences can connect with.

Strong singing

Davronov sang strongly, with a ringing tone that matched well with Galoyan in their duets. If his acting was stiff in the country house scene, that is partly due to the limited space in the set. He sang with great expression and his tragedy was palpable by opera’s end.

Costumed as a military officer, Daza was an imposing figure, and his large baritone voice commanded the stage from his entrance. He was never a sympathetic figure in his long scene with Violetta, but he is not meant to be. Booked for Dulcamara in l’Elisir d’amore, he has sung Germont before and so was an obvious person to take over the role, which he filled admirably.

Sejin Park was appropriately arrogant as Baron Douphol. Elisa Sunshine sang well and understands her limited role as Violetta’s faithful maid Annina. Kaylee Nichols has a strong voice but didn’t seem quite dissolute enough for the scandalous party-loving Flora Bervoix.

The orchestra played admirably, following Rovaris’s expressive rubatos and supporting the singers well through the softest moments. The party-scene choruses were full voiced and strong, contrasting powerfully with the delicate and reflective moments of the lead singers—another level of contrast between the public and private lives of the characters.

This production, and the performance I saw, would stand out in anyone’s season. In a long history of memorable operas at Santa Fe, it is a production worth seeing and remembering.

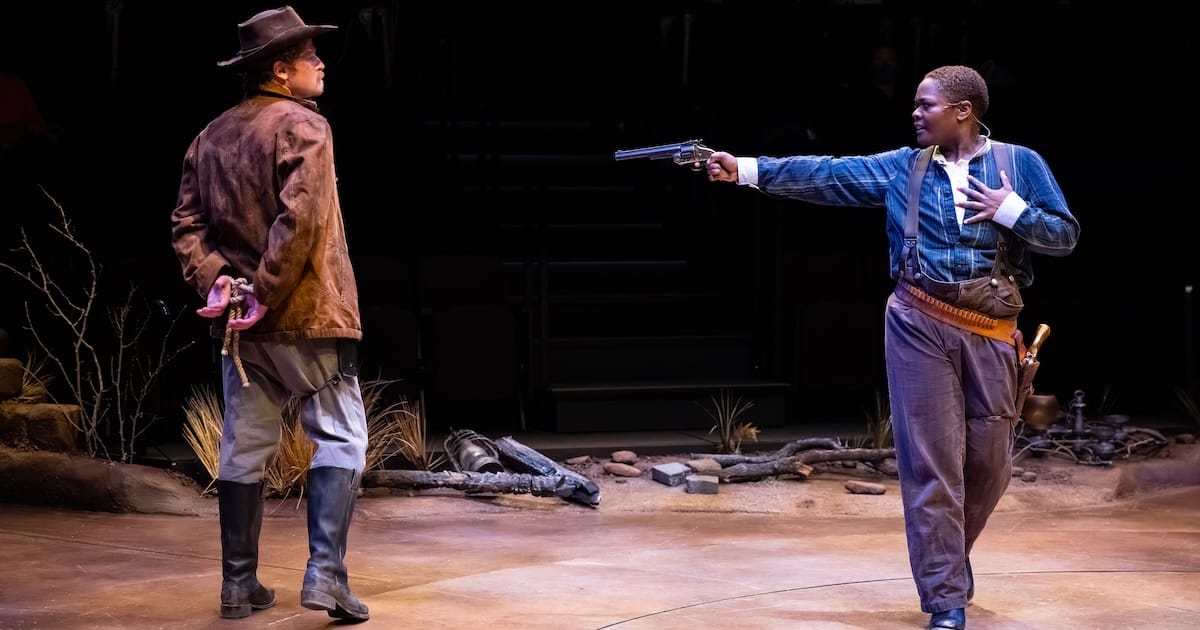

Rachel Fitzgerald (Opening night Donna Anna), Ryan Speedo Green (Don Giovani) and David Portillo (Octavio) in ‘Don Giovanni’ | Photo by Curtis Brown.

Don Giovanni

The production of Mozart’s Don Giovanni has been transported to Victorian-era London. In some ways this works well, but in other ways, not.

The updating was inspired largely by the coincidence that Don Giovanni and Dorian Gray of Oscar’s Wilde’s novel The Picture of Dorian Gray share the initials DG, and that both pursue a life of hedonism. Beyond those superficial similarities, it is certainly true, as director Stephen Barlow points out in his notes, that both the world of Don Giovanni and Victorian England were class-bound societies.

In the opera, each member of the cast is defined by their standing as nobility or peasantry, impenetrable social levels identified in the music. These musical distinctions put class, which would have been immediately clear to Mozart’s audience, at the heart of the opera, as it was to lives in Victorian England.

But in other ways, the updating is less successful. To maintain the transformed setting, Don Giovanni sings “Come to your window, my treasure” sitting in the lobby of a posh hotel. Instead of a graveyard, Giovanni “leap(s) over the wall” into an enclosed funeral parlor. And in a particularly baffling decision, there is no statue, only a casket sitting on a pedestal.

Leporello sings of the immobile casket, “He looked at us.” There is no statue at all — a consistent feature of Don Juan mythology for centuries — in the final scene. The Commendatore enters through a picture frame as a ghost, again making nonsense of the sung text.

Some of the seat-back English titles strayed from the literal to contribute to the Victorian ambience. “Listen, guv,” Leporello sings to Giovanni, and the “Champagne Aria” — literally “As long as the wine warms the head” — has no mention of wine.

One other quibble: If Giovanni is an English Lord ravishing the women of London, why is England not mentioned in Leporello’s “Catalogue Aria”? And what’s the big deal with Spain? Or do we not expect the stage action to correspond to the text in concept productions?

Musical performance

But the musical performance was strong throughout. Conductor Harry Bicket led a stylish if unhurried performance, sometimes bordering on sluggish. To its credit, the orchestra followed his expressive direction faithfully. Once under way, the strings played with clean ensemble, and the horns sounded particularly bright.

Ryan Speedo Green, one of the leading baritones worldwide, was an ingratiating, seductive Giovanni. His voice, while used expressively, is almost too strong for the part. At times he struggled to keep it under control, and balance with Zerlina and other light-voiced characters was occasionally askew. He delivered all the hedonistic enthusiasm needed for the “Champagne Aria,” and made Giovanni a totally assured libertine.

Rachel Willis-Sørensen, engaged for the the Marschallin in Der Rosenkavalier and standing in as Donna Anna, was another singer who seemed at times out of her fach. Her strong, steely voice tended to get away from her at phrase climaxes, but she effectively conveyed the opera’s most tragic character. She was equally capable of expressively weighty tones and pure, bright high notes.

Rachel Wilson’s Donna Elvira was the very essence of the scorned woman. Her dramatic performance and assured singing made Elvira the central character of the unfolding drama, both strong in her confrontations with Giovanni and tragic in her repeated humiliations. She handled the seria aspects of her role with aplomb, with a few stumbles across registers.

Nicholas Newton provided a good comic performance as Leporello. His “Catalogue Aria” was thoroughly entertaining, as he embraced the comic emphasis of the production. David Portillo’s pleasant, light tenor is well suited to the role of Don Ottavio, even though he showed signs of fatigue by the end of a very long opera.

Liv Repdpath was a sweet voiced Zerlina, capturing the character’s innocence well. William Guanbo Su portrayed an angry Masetto whose reconciliation with Zerlina seemed out of reach until the very end. Solomon Howard’s rotund bass suited the Commendatore perfectly.

Other notes on the production: a creative set with rotating panels created seamless scene transitions. Don Giovanni’s salon, with walls covered in portraits of the Don recalled the production’s inspiration in The Portrait of Dorian Gray at the same time that it confirmed Giovanni’s narcissism.

A red spot on the floor, marking where the Commendatore dies in the first scene, became a meaningful symbol. From one scene to the next, efforts to scrub it out always failed.

Barlow’s production stressed the comic elements of the plot — the opera is labeled a drama giocoso, “comic drama” — but sometimes the resort to burlesque distracted from the singing. The most egregious example was the beginning of Act II, where some clumsy humor with luggage in the background distracted from Elvira’s mournful “Ah taci, ingiusto core.”

I’m not sure what the British Bobby contributes to the last scene, except that it recalls Ottavio’s promise to bring Giovanni to justice. Which raises the question: Is the Victorian setting, evoked by Bobbies and street lamps as well as costumes, too familiar to audiences from television? This is not Downton Abbey. I wonder what expectations are raised with such clear signposts in the production.

Peter Alexander holds a Ph.D. in musicology from Indiana University. He is retired from the University of Iowa, where he was director of media relations for all the arts organizations on campus for 23 years. Since his retirement he has written for Boulder Weekly, and currently writes news stories and reviews of classical music for his blog, Sharpsandflatirons.com. He is also principal clarinet for the Longmont Concert Band, and worked for many years as a church choir director.

Leave A Comment