The century-old play rings eerily prescient in our age of AI.

Springs Ensemble Theatre (SET) has reached 100 years into the past to find a play apropos to our times: R.U.R., by Czech writer Karel Čapek. Written in 1920, the science fiction work introduced the term “robot,” which Čapek derived from a Czech word meaning serf or forced labor, into our lexicon.

Matt Phillips, who directs SET’s production, adapted the play, which tells the story of Rossum’s Universal Robots. The company, located on a remote island, manufactures robots to make life more efficient, less tedious. Helena Glory (Sheridan Singer), of the “Alliance for Humanity” visits the island to advocate for humanity and robots but ends up staying and marrying R.U.R’s executive, Harry Domin (Ethan Everhart).

The lead scientist, Dr. Gall (Daniel Salamé), conducts rogue experiments which, in making the robots more human-like, gives them the capacity to rebel against their human masters. They do, successfully, with one limitation: They are unable to replicate themselves and it turns out the original plans for their design have been destroyed.

The play piles irony upon irony as it explores what it means to be human — and what it means to be a machine. The parallels are underscored by double-casting roles: Five of the six actors playing human characters also play robots.

The cast is uniformly excellent. As Helena, Sheridan Singer commands the stage, ranging easily from skeptical to sweet to fiery anger. As the abruptly paired Domin and Helena, Everhart and Singer have an engaging flirtatious rhythm. The always authentic Robert Sherrane, as Mr. Alquist, the resident skeptic of R.U.R.’s ambitions, closes the play on a note that is both poignant and hopeful.

Phillips adeptly moves characters around the stage, choreographing Domin and Helena’s meeting to show the relationship move from initial distrust, hostility and eventual attraction.

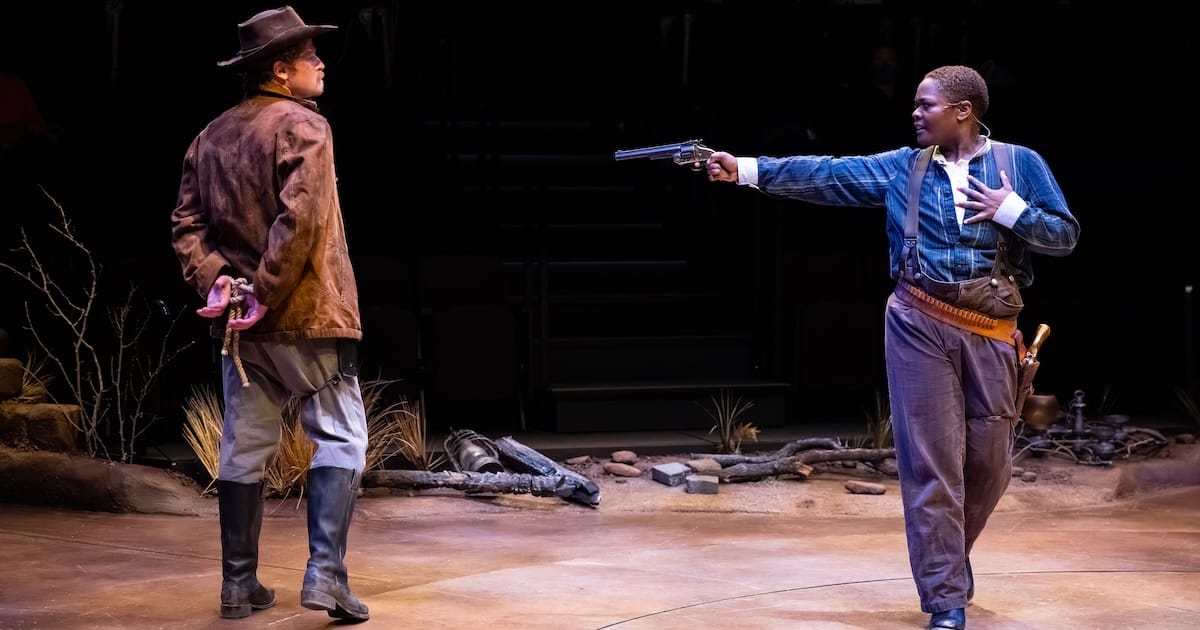

It’s a show with a surprising amount of action, given SET’s tiny stage. Allyson Hackworth, who also acts the twinned roles of Nana/Sulla, choreographs the robot takeover as an interpretive dance. It’s a much better choice than stage fighting and further establishes the play’s quasi-fantasy world.

The set design, by Josh White, features gray cinderblock walls, immediately giving an impression of dull imprisonment.

The costume design is not as successful. There’s a clear contrast between robots in blue uniforms versus the varied outfits of humans that works well. But the human costumes don’t portray a specific era. Some of the suits and ties could be early 20th century, others seem more mid-20th. This may be purposeful or a budgetary issue, but it doesn’t create a sharp or consistent image.

As usual with SET productions, the crew work is exemplary. For example, the fireplace where Helena makes the fateful decision about robot designs creates satisfying flares for this pivotal moment.

In his Director’s Note, Phillips argues that R.U.R. is less about “technology” than about human alienation. The robots, he argues are “representative of people who have been disconnected from their humanity by the demands of their work.”

The play certainly poses questions that stick with you. “You do unnecessary things,” the robot, Radius (Elijah Field), says to a human. It’s an accusation. This is a night at the theatre that demonstrates how important the unnecessary really is.

Judith Sears has had a 25-year career in marketing and corporate communications. Over the last several years, she has pursued playwriting, and several of her short plays have received staged readings at Colorado theatres.

Leave A Comment