Upstart Crow’s tense, thoughtful A Few Good Men features standout performances and sharp casting, despite some community theatre bumps.

Theatres across Colorado are knee-deep in holiday cheer right now, but Boulder’s Upstart Crow has gone in a different and far gutsier direction.

Their staging of Aaron Sorkin’s A Few Good Men digs into war crimes, chain-of-command ethics and the high cost of blind obedience. And in a year marked by renewed scrutiny of military power (yes, I’m looking at you, Pete Hegseth, and the ongoing investigations into allegations of multiple war crimes), the material feels uncomfortably, undeniably timely.

This is, by far, the strongest work I’ve seen from Upstart Crow. It’s not flawless; some pacing issues and technical inconsistencies keep it from being the taut thriller it wants to be, but the performances are so compelling, and the moral stakes so vividly drawn, that the production lands with surprising force.

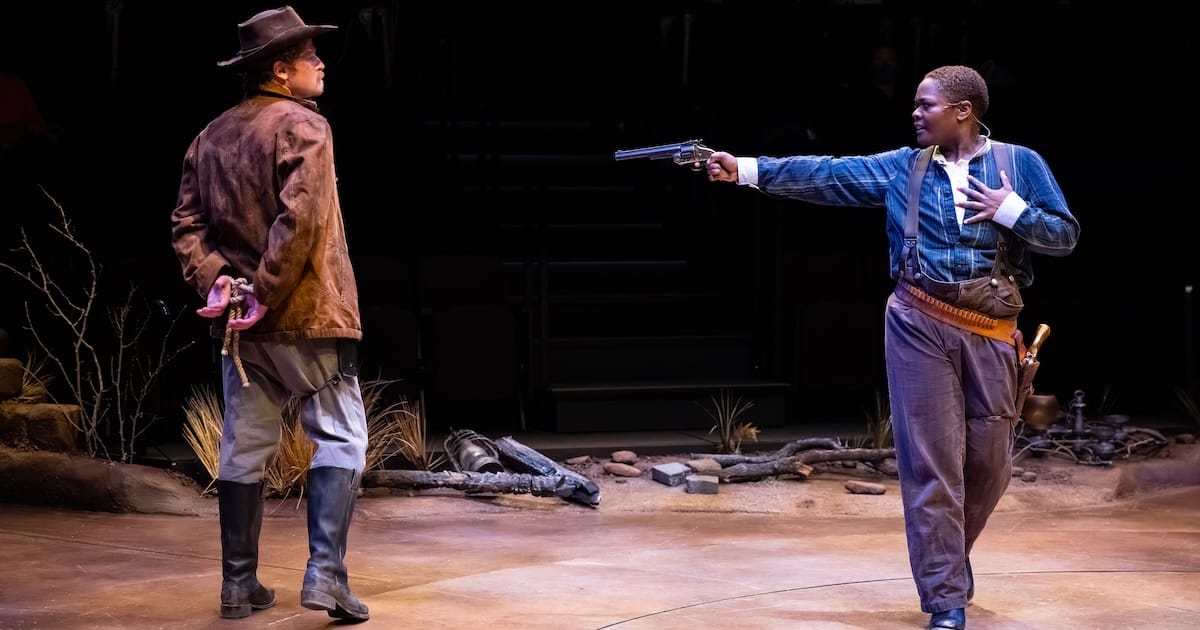

Photo: Joseph Bowman

A dynamic trio carries the drama

Before it became a blockbuster movie in 1992 starring Tom Cruise, Demi Moore and Jack Nicholson, A Few Good Men was Sorkin’s breakout stage play. Written in 1989 and drawn from his own sister’s experiences as a JAG lawyer, the script follows young Navy attorney Lt. Daniel Kaffee as he defends two Marines accused of murdering Private William Santiago at Guantanamo Bay.

What begins as an open-and-shut case quickly reveals layers of command pressure and a culture that rewards obedience over moral clarity. The courtroom becomes a battleground where the military’s rigid hierarchy collides with personal conscience. The story’s questions about who holds power, who is accountable for military actions and who is sacrificed when times are tough have only grown sharper over time.

What elevates this staging of A Few Good Men directed by Ed Castaldo is its core trio leading the charge: T.J. Jackson as Lt. Daniel Kaffee, Kamari Schneider as Sam Weinberg and Jordan Hull as Joanne Galloway. The trio’s natural chemistry alternates between playful, combative and supportive, but it is always deeply felt.

Jackson, a recent transplant after a decade in Atlanta’s film and theatre scene, is a revelation. His Kaffee begins as a breezy, dismissive nepo baby coasting through Navy life, but Jackson slowly uncovers the grief and insecurity lurking beneath the swagger. As the case forces Kaffee to confront his father’s legacy and his own complacency, the actor delivers a riveting blend of charm, anguish and righteous determination.

Schneider, as the exasperated and frequently hilarious Weinberg, grounds the show with deadpan realism. He portrays Weinberg as a tired father who would rather be at home with their newborn child but is reluctantly working on the case with Kaffee. Their skepticism about defending two Marines who beat up someone weaker than them gives the play needed moral friction.

Hull, meanwhile, is forceful and precise as Galloway. Hull is assertive, vulnerable and deeply attuned to the sexism baked into her environment. Her scenes with Jackson crackle with tension: they challenge each other, frustrate each other and ultimately inspire each other to give a damn.

As the defendants, Danice Crawford (H.W. Dawson) and Joshua Raine (Louden Downey) handle their subtler roles with grace, especially Crawford, who charts a slow, steady shift from icy distrust to hard-earned respect with Kaffee.

Photo: Joseph Bowman

Inspired casting deepens the political stakes

I don’t usually comment on casting beyond performance quality, especially in community theatre, but here it feels impossible and irresponsible not to. In Upstart Crow’s production, Kaffee, Galloway, Weinberg and Santiago (Adaly Gonzales) are played by actors of color, while the Marine brass remains entirely white. Sorkin’s script never directly frames its conflict around race, but when embodied this way, the power dynamics of the piece shift in deeply compelling and unsettling ways.

Suddenly, the story’s examination of authority isn’t just about military bureaucracy — it echoes the very real history of who gets protected, who gets punished and who gets sacrificed in American institutions.

That resonance is clearest in Joseph Bowman’s chilling performance as Kendrick. When he delivers the line, “I don’t like you people,” it no longer reads as a broad disdain for lawyers but instead lands as a dog whistle loaded with racial animus. And when Sky Michaels’ Jessup mocks Kaffee’s “faggoty white uniform,” demanding that his “Harvard mouth extend me some fuckin’ courtesy,” the exchange not only reveals hierarchical dominance but also evokes decades of racialized expectations around respectability and assimilation.

For a community theatre production, it’s surprisingly layered, and it adds a dimension of political and emotional immediacy that I wasn’t expecting going in.

Uneven execution with a powerful finish

Upstart Crow’s design approach shows real ambition, even if the technical execution doesn’t always rise to the level of the performances. Scenic designer Kamari Schneider’s thrust staging, with its elevated judges’ platform and patriotic lighting palette, succeeds in giving the courtroom scenes a sense of institutional weight.

However, Castaldo’s direction could have used more crossfades in the lighting design to keep the pace up, as transitions sap momentum. Some scenes transition smoothly from one to the next with no pause, while others completely halt the action with long pauses to move furniture or sudden blackouts that appear more accidental than intentional.

These inconsistencies make Sorkin’s already sprawling play feel even longer, especially in Act II, where several jumped cues, missed lines and uncertain entrances further stall the pacing.

The costumes by Melissa L. B. Castaldo similarly reveal aspiration outpacing resources. While the principal cast looks appropriately outfitted, several supporting characters appear in mismatched or incomplete uniforms, including most noticeably a pair of modern tennis shoes on a supposedly regulation-obsessed Marine officer. It’s a small detail, but in a play built on questions of discipline, authority and image, it stands out.

Logan Foy’s lighting design is effective in group scenes and scenes staged around the elevated platform up center, but it frequently casts actors in shadows during intimate or emotionally charged moments that are blocked center stage.

Some performances also fall on the flatter side. Billie Bowman’s judge, though effective when leaning into the character’s dry authority, is often difficult to hear and doesn’t maintain the energy the role demands. A few supporting actors struggle with diction or stiffness, particularly in the second act’s procedural scenes, where the tempo should accelerate rather than drag.

Yet despite the bumps, the production’s final stretch lands with undeniable force. The climactic face-off between Jackson’s Kaffee and Michaels’ Jessup, which is arguably the reason people come to this play, crackles with tension. Jackson builds to the moment with clarity and conviction, and Michaels meets him beat for beat, delivering “You can’t handle the truth!” in a way that honors the iconic line without descending into imitation.

It’s a thrilling, brutal, cathartic payoff that feels fully earned. And that’s ultimately where this A Few Good Men succeeds most: in its heart, its casting choices, its performances and its willingness to grapple sincerely with one of Sorkin’s most morally loaded stories.

The technical flaws are real and worth addressing, but they don’t overshadow the production’s ambition or its flashes of true excellence. If Upstart Crow can bring this level of acting and political clarity to future work while tightening the fundamentals, they’ll be poised to produce genuinely remarkable community theatre. For now, this is a compelling and, unfortunately, timely drama that’s well worth stepping away from the holiday glitter to see.

A Colorado-based arts reporter originally from Mineola, Texas, who writes about the changing world of theater and culture, with a focus on the financial realities of art production, emerging forms and arts leadership. He’s the Managing Editor of Bucket List Community Cafe, a contributor to Denver Westword and Estes Valley Voice, resident storyteller for the Bonfils-Stanton Foundation and co-host of the OnStage Colorado Podcast. He holds an MBA and an MA in Theatre & Performance Studies from CU Boulder, and his reporting and reviews combine business and artistic expertise.

Leave A Comment