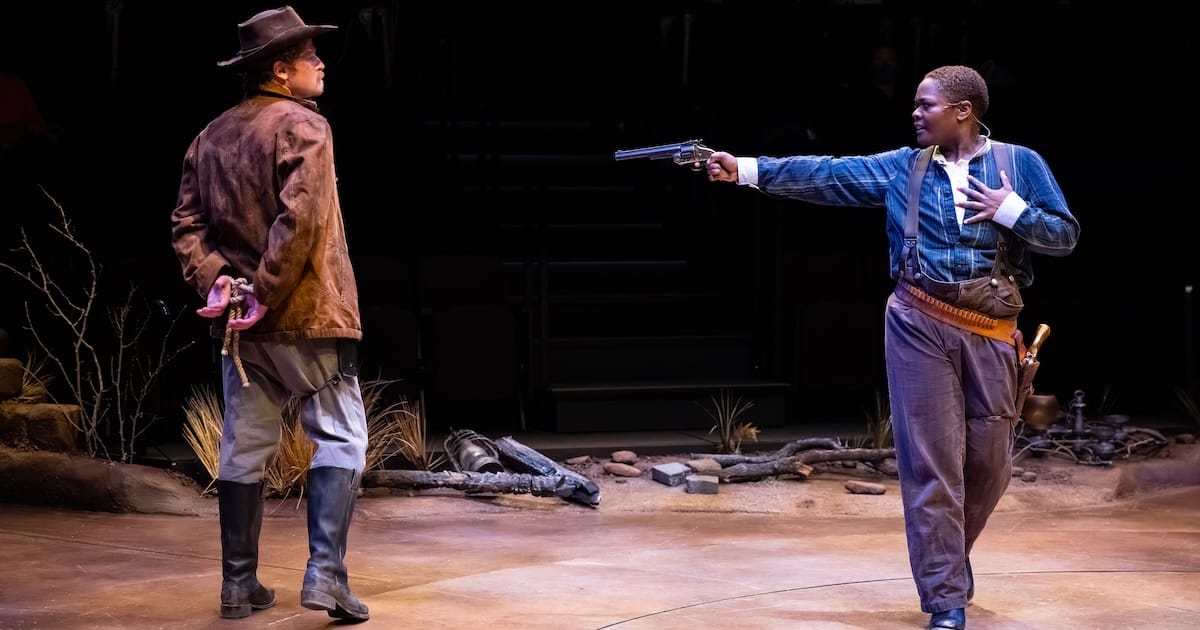

While moments shine, the production struggles to capture the feral energy Clare Barron’s script demands.

It’s easy to see why Phamaly Theatre Company chose to produce Clare Barron’s Dance Nation. The Pulitzer Prize–nominated play follows a troupe of preteen dancers in middle America as they claw their way toward national finals in Tampa Bay. Beneath the sequins and sweaty rehearsals lies a sharp examination of the terrifying transition from childhood to adulthood and the desperate hunger to be seen.

For a company dedicated to challenging expectations and giving performers with disabilities the space to shine, Barron’s wild, subversive script is an ideal match for Phamaly. But under GerRee Hinshaw’s direction, this Dance Nation feels curiously muted.

Barron insists in her script that the dances should be “terrifying rituals that conjure real power” and that performers embrace “Pagan feral-ness and ferocity” rather than “cuteness.” Instead of ritual and danger, the choreography and staging settle for restraint and naturalism. It’s an oddly safe approach to a play that thrives on chaos and uncomfortable truths.

Direction that holds back

The evening begins with a cheeky parody of Anything Goes, setting up expectations for the choreography to evolve into something stranger and more primal as the story unfolds. Yet Savannah Svoboda’s choreography remains cutesy, with only flashes of animalistic movement.

At moments, the cast dons plastic teeth to signal a transformation into beastly dancers, but the gesture feels like a surface-level choice rather than an embodied, ritualistic shift in performance. Hinshaw’s choice to underplay the surrealism blunts the script’s sharpest edges and slows its pace, leaving scenes that should feel charged with danger oddly subdued.

The same flattening affects key moments of discomfort. Dance Teacher Pat (B Glick), a character who should be both mentor and menace, is played broadly, reducing the complexity of their unsettling role. A scripted moment in which Pat makes a pass at a student barely registers, stripped of the disturbing ambiguity Barron builds into the text.

Time and again, the production opts for restraint where provocation is called for, leaving much of the production feeling more like a quirky dramedy than a feral coming-of-age fever dream.

A mixed ensemble

The play’s heart beats in the rivalry between Amina (Cass Dunn) and Zuzu (Clara Papula), two teammates vying for the role of Gandhi in their competition dance. Dunn’s Amina buzzes with nervous energy, twitchy and over-the-top in a way that channels Barron’s intended surrealism. Papula, by contrast, plays Zuzu with a more subdued, self-pitying quality.

The clash of styles makes their dynamic feel uneven and their rivalry less combustible than it should be. Compounding this, Papula stumbled on a few opening-night lines, which further muddled the chemistry between the pair. Their conflict — meant to drive much of the play’s tension — often felt flat, predictable and underdeveloped.

The ensemble’s smaller interactions with one another feel more alive. Atlas Drake shows versatility as both the sidelined dancer Vanessa and a carousel of dance moms, moving fluidly between comedy and tenderness. Kendall Malkin (Makenna), Annie Sand (Sofia), and Phoenix Mehta (Connie) add energy in group scenes, where their background banter feels spontaneous and believable. Sand, in particular, excels at delivering biting one-liners and later provides much-needed depth in her Act II scene, where she learns about menstruation.

Artie Thompson shines as Maeve, the team’s oldest and least talented dancer. Thompson’s vulnerability and comedic timing provide some of the show’s most heartfelt moments, particularly in her exchange with Zuzu in Act II, when she tries to encourage her while giving a speech about how she can fly now but will forget about it when she grows up.

B Glick struggles to add complexity to Dance Teacher Pat. Played as a character always seconds away from yelling, their performance flattens the character into an exaggerated stereotype. What should be an ambiguous, unsettling presence is instead portrayed as a one-note authority figure.

Keenan Gluck fares better as Luke, the lone boy on the team. Gluck consistently earns laughs through sharp reaction work, especially when placed amid the girls’ raw, unfiltered conversations. His understated humor provides welcome levity, even if the production never fully develops Luke beyond a foil for the ensemble.

The evening’s high point belongs to Lily Blessing as Ashlee. Her reactions throughout the show are some of the sharpest, and the blistering monologue Blessing performs about being destined for greatness in Act I — which the deaf actor signed with projected captions behind her — commands the stage with a ferocity lacking in the rest of the show.

Blessing’s performance, layered with moments of rage, cockiness and tenderness, made the audience lean in and, for a few minutes, captured the dangerous, ecstatic power Barron’s script demands. It’s the one scene that feels fully alive, as if the production briefly lets itself off the leash.

Not quite unhinged enough

The design team keeps the production polished but never lets it spiral into the theatrical excess the script craves. Svoboda’s choreography sets the production’s cautious tone. While clear and cleanly executed, the dances rarely push past simplicity. Only occasionally does the movement edge toward the surreal, and even then, it feels tentative.

The production design mirrors this restraint. Amanda Fisk’s lighting provides crisp isolations and colorful washes during dance numbers, but the shifts remain tidy rather than explosive. Alex Romberg’s sound design lands well with clean cues and background texture, and Susan Rahmsdorff-Terry’s costumes cleverly walk the line between adolescent sparkle and grounded realism.

As always, Phamaly integrates accessibility with care and artistry. Captions run throughout, ASL is embedded into the performances and sensory accommodations are offered at every show. These choices expand the theatrical language of the piece.

In Ashlee’s monologue especially, the interplay of signing and projected text heightened the defiance and scale of the moment. However, the production could have gone a step further; scenes in which deaf actors signed, and captions translated their words sparkled with theatrical charge, whereas scenes that played as straightforward realism without engaging the actors’ disabilities felt comparatively flat.

Dance Nation is meant to feel like adolescence itself: grotesque, ecstatic and out of control. Phamaly’s production, though dotted with standout performances and thoughtful accessibility, too often reins in the chaos. What emerges is an intriguing but overly careful take on a play that should leave the audience unsettled and breathless.

There are flashes of brilliance, particularly in Blessing’s galvanizing monologue and Thompson’s endearing performance, but they remain exceptions rather than the rule. Ultimately, Hinshaw’s Dance Nation gestures toward Barron’s ferocity but never fully dances into it.

A Colorado-based arts reporter originally from Mineola, Texas, who writes about the changing world of theater and culture, with a focus on the financial realities of art production, emerging forms and arts leadership. He’s the Managing Editor of Bucket List Community Cafe, a contributor to Denver Westword and Estes Valley Voice, resident storyteller for the Bonfils-Stanton Foundation and co-host of the OnStage Colorado Podcast. He holds an MBA and an MA in Theatre & Performance Studies from CU Boulder, and his reporting and reviews combine business and artistic expertise.

Leave A Comment