Director Melissa Lucero McCarl helms a timely, stirring regional premiere about censorship, race and resilience in 1950s Alabama.

In today’s media landscape, the conflict at the heart of Alabama Story would be branded a “culture war.” A children’s book about two rabbits, one black and one white, getting married sparks outrage, politicians rush to exploit it, and a librarian finds herself at the center of a storm she never asked for.

Though the play is set in 1959, Firehouse Theater Company’s regional premiere makes it clear how little the rhetoric of censorship has changed. Directed by Melissa Lucero McCarl, Kenneth Jones’s play lands with the sting of a contemporary editorial, dramatizing how battles over books are rarely about literature and always about power.

Firehouse, the Denver troupe based in the Lowry neighborhood, known for punching above its weight in the intimate John Hand Theater, continues its streak of strong dramas with this production. McCarl directs the staging with clarity and restraint, ensuring that there is never a dull moment throughout the two-and-a-half-hour production.

Set in Montgomery, Alabama, the play dramatizes the true story of Emily Reed, the state librarian who found herself at the center of a political firestorm when segregationist lawmakers sought to ban The Rabbits’ Wedding, a children’s book that dared to depict a black rabbit marrying a white rabbit.

In the program note, McCarl cites playwright Kenneth Jones’s own description of the play as “a play about white people who poisoned the world, and those who worked to neutralize the poison.” That framing positions Alabama Story not simply as a Civil Rights tale with a censorship subplot, but as a meditation on how censorship itself becomes a tool of systemic racism.

It’s a perspective that feels eerily in step with our own time, when debates over what books and ideas belong in the public sphere once again dominate headlines.

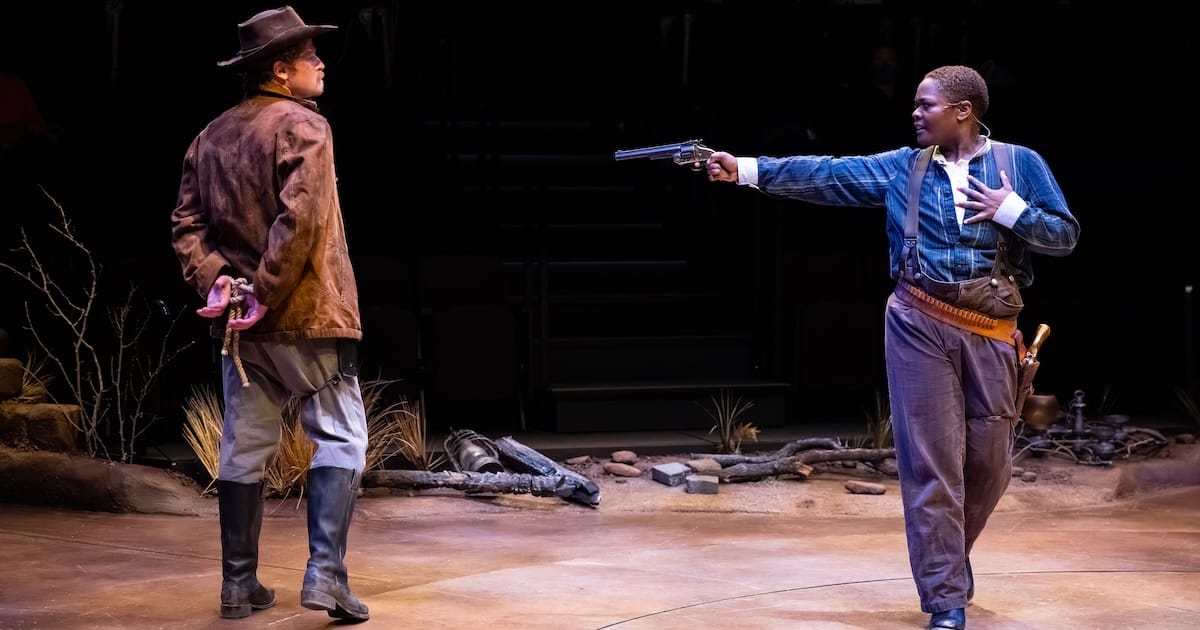

Lilly Whitfield (Elicia Hesselgrave) and Joshua Moore (Jysten Atom) | Photo: Soular Radiant Photography

A librarian’s fight

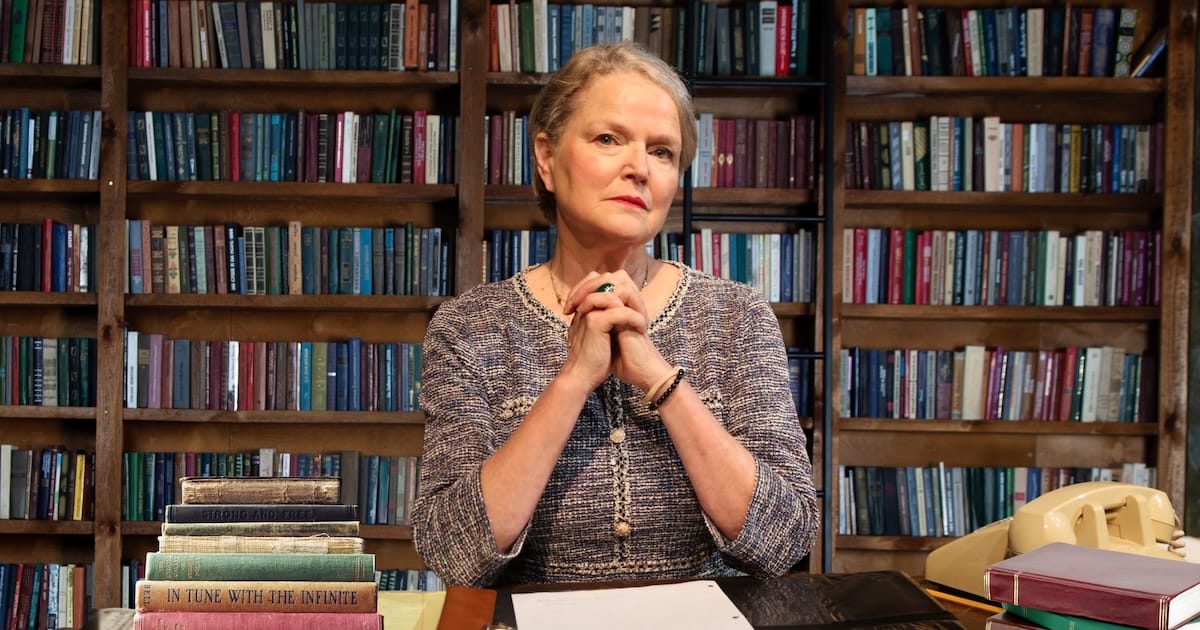

At the heart of the play is Emily Reed, the head librarian of Alabama who dared to include The Rabbits’ Wedding in the state system. Martha Harmon Pardee captures Reed’s no-nonsense personality with remarkable subtlety.

Reed is no fiery activist, but a competent civil servant caught in a political maelstrom. Pardee wisely avoids turning her into a didactic crusader. Instead, she portrays Reed as a woman simply doing her job. It’s an understated but deeply human performance, grounded in her integrity rather than grand speeches.

Her foil and confidant is Thomas Franklin, Reed’s assistant, played with jittery charm by Cal Meakins. Where Reed is reserved, Franklin is fretful, high-strung and quietly hiding his own secret. Their dynamic — she the pragmatic straight woman, he the slightly neurotic but fiercely loyal subordinate — anchors the production. Their affection for each other, conveyed in glances and subtle exchanges rather than overt declarations, lends the play a poignant core.

If Reed is the conscience of the piece, Senator E.W. Higgins embodies its corrupting force. Matt Hindmarch, a standout Colorado character actor, makes Higgins smarmy, funny and chilling. He is a man whose charisma almost conceals his cruelty, which is precisely what makes him dangerous.

Guiding us through the story is the creator and illustrator of The Rabbits’ Wedding, Garth Williams, portrayed by Jeff Jesmer. In McCarl’s staging, Williams becomes both narrator and theatrical trickster, orchestrating lights and transitions like a godlike stage manager.

At times, this device feels heavy-handed, and the conceit of Williams as an all-seeing guide is somewhat repetitive after its initial reveal. Still, Jesmer’s versatility as he inhabits multiple supporting roles, including politicians, townspeople and bystanders, adds texture to the world and underscores the ripple effects of one book’s suppression.

Running alongside the political drama is the quieter, more intimate subplot of childhood friends Joshua Moore (Jysten Atom) and Lilly Whitfield (Elicia Hesselgrave). Joshua, a Black man, and Lilly, a white woman of privilege, reunite and confront the scars of their shared past. Joshua reminds Lilly of her father’s brutality when their youthful closeness was discovered, while Lilly clings to selective memory.

Their scenes, staged at a locked park bench, sharpen the play’s themes of denial and complicity. That said, the subplot does not always integrate seamlessly with the main action. Hesselgrave’s accent veers toward caricature, even as she nails the performative sweetness of Southern gentility. Atom plays Joshua with quiet dignity, though the chemistry between them lacks the spark implied by the text.

Still, the storyline provides necessary contrast: a reminder that systemic battles are mirrored in personal lives.

Winning design

McCarl and her creative team make excellent use of the John Hand Theater’s small space, carving out three distinct playing areas: Reed’s office on stage left, the segregated park on stage right, and a central stairway flanked by columns that flexibly transform into various settings.

One of the most striking moments arrives early, when ensemble members ritually “build” Emily Reed’s identity by handing her objects, unveiling a floor painting of the book’s cover in the process. The sequence recalls Greek theatre and immediately invests the audience in the symbolic stakes.

Rachel Herring-Luna’s costumes evoke period authenticity, while Madison Kuebler’s sound design and transition music immerse us in the Southern atmosphere. Emily Maddox’s lighting blends seamlessly with Jesmer’s narrator role, while props by Maru Garcia and scenic painting by Megan Davis give the production its tactile sense of place.

The design is never flashy but consistently serves the storytelling.

Emily Reed (Martha Harmon Pardee), Thomas Franklin (Cal Meakins) and Senator E.W. Higgins (Matt Hindmarch) | Photo: Soular Radiant Photography

A timely regional premiere

Though over two hours, McCarl’s efficient pacing, combined with nuanced performances, keeps the audience engaged. And the play’s central message — that censorship is never neutral and always tied to deeper structures of power — rings with urgency.

What stands out the most is how deftly McCarl uses Firehouse’s intimate space to amplify the script’s themes: The cluttered librarian’s office feels like a battlefield, the locked park gate represents exclusion and the painted children’s book cover represents the innocence that bigotry seeks to erase. It’s a clever, efficient use of the venue, maximizing the small space to create a theatrical, magical and politically resonant regional premiere.

In a season stuffed with Halloween frights, Alabama Story reminds us that some of the scariest battles aren’t waged with monsters, but with ideas — and who gets to decide which ones we’re allowed to read.

A Colorado-based arts reporter originally from Mineola, Texas, who writes about the changing world of theater and culture, with a focus on the financial realities of art production, emerging forms and arts leadership. He’s the Managing Editor of Bucket List Community Cafe, a contributor to Denver Westword and Estes Valley Voice, resident storyteller for the Bonfils-Stanton Foundation and co-host of the OnStage Colorado Podcast. He holds an MBA and an MA in Theatre & Performance Studies from CU Boulder, and his reporting and reviews combine business and artistic expertise.

Leave A Comment