The regional premiere of Job is a tense, 80-minute psychological showdown powered by Tuuli Sandvold’s riveting performance.

Max Wolf Friedlich’s Job may share a title with the biblical epic of suffering, but Curious Theatre’s regional premiere plays more like a white-knuckle psychological thriller than a morality tale. Directed with stealthy precision by Josh Hartwell, this tight, intermission-less two-hander transports audiences to a San Francisco therapist’s office in January 2020, where the tension is constantly ratcheting up until the play’s chilling final blackout.

If real-life work can be a chore, Job is anything but. Curious Theatre’s production is brisk, brutal and intellectually gnarly, anchored by a fierce, ceaselessly alive performance from Tuuli Sandvold as Jane, a tech content moderator who arrives at her mandated therapy session vibrating with fear, fury and something more dangerous.

Before we can even orient ourselves, Jane is holding a gun to the head of her therapist Loyd, played by Michael Morgan, demanding he not speak. That moment, accompanied by Jon Olson’s abrupt lighting snaps and Max Silverman’s dissonant sound cues, quickly dissolves into darkness.

Another flash: Loyd tells her, “You did it. You were right about everything,” before he lunges at her. Another flash: it’s a normal first therapy appointment where Loyd discusses Jane’s “parking pass.” Another flash: Jane is holding Loyd hostage before turning the gun on herself. Another flash: only then do we land in what appears to be the real session, Jane again pointing a gun but panic flooding her face as she realizes she’s woken from a trance.

These jagged temporal fractures recur throughout the play. Whenever Jane’s mind spirals, the lights and sound carve open a fissure. It’s a device that occasionally feels heavy-handed but undeniably builds the queasy uncertainty that defines the experience: Jane is an unreliable narrator, and Loyd may be an unreliable authority.

Brian Watson’s scenic design reinforces the play’s grip on reality. Loyd’s therapist’s office, featuring a rumpled couch, a well-worn chair, a desk cluttered with papers and screens, a Grateful Dead poster and tons of trinkets on his bookshelves, looks lived-in and disarmingly ordinary. Against this hyper-naturalistic backdrop, the bursts of psychological horror Jane experiences hit even harder.

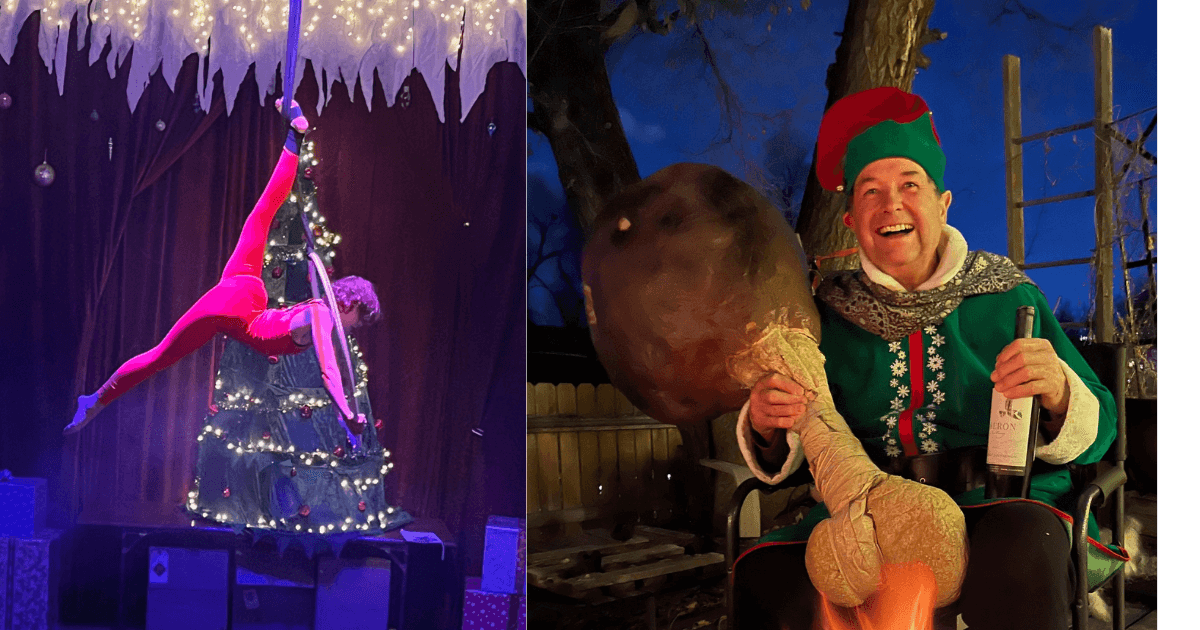

Tuuli Sandvold and Michael Morgan in ‘Job’ | Photo: Amanda Tipton Photography

A content moderator on the brink

Once the initial shock settles, Jane immediately announces she has no interest in therapy. “It’s the field that’s the problem,” she says. “Because people with your job come into work so desperate to connect Trauma A to Trauma D so they always do.”

Jane has been placed on leave after her meltdown at work went viral, so she needs Loyd to approve her return to work but stresses that she isn’t here of her “own free will.” Jane is “here because of my job.”

Sandvold never stops vibrating with kinetic energy. She taps, paces, interrupts Loyd mid-sentence, and ricochets between biting cynicism and open grief. She’s whip-smart and blisteringly funny, tossing off lines like, “Everyone’s racist and we’re all alone. That’s sort of our brand in 2020 as humans,” with such dry precision that the audience winces even as it laughs.

But she’s also haunted by her Wisconsin childhood, her artist father whom she calls weak, a college affair with Sid that ended in a secret abortion, and, perhaps most of all, the images she was paid to moderate. Those images of mass graves, sexual abuse and grotesqueries dredged from the internet underworld are seared into her brain. Even after being fired, Jane can’t stop looking for the bad people she saw on her work screen.

That hunger for power becomes her defining trait: Jane wants control in a world where she has almost none. Sandvold plays her not as a victim of circumstance but as a woman who refuses to accept powerlessness, even if it means bending truth or perception until something breaks.

Opposite Sandvold, Morgan’s Loyd is all soothing tones and gentle authority at first, as a therapist who believes he’s uniquely equipped to help people no one else can reach. He reveals he was previously married, that he has two children (a boy and a girl), and that his daughter died by suicide at 13.

These details are delivered lightly, almost clinically, but every time a fact about Loyd’s past slips out, the lights flicker, the sound snarls and Jane’s body stiffens. She thinks she’s heard this before … online.

Jane eventually claims that Loyd is the father from a horrifying incest video she found online: a man who forced his children to have sex, filmed it, posted it, and, after his daughter’s suicide, filmed new acts with his son. The accusation hits like a grenade, propelling the play to its climax.

Morgan’s performance is strongest when he tries to maintain control, listening intently, soothing gently and rationalizing calmly, but when he’s scripted to panic, his performance feels slightly less convincing. His fear never fully erodes that calm therapeutic façade. More emotional contrast from Morgan’s performance in scenes where he truly fears for his life would add to the cat-and-mouse dynamic, especially as Jane tightens her grip on the situation.

Nonetheless, the pair’s chemistry as two people with vastly different ideologies and motives is largely effective. Their rhythm, tension and charged verbal sparring keep the play together with remarkable intensity.

A finale that will leave you talking

The script smartly refuses to adjudicate the truth. Is Loyd a monster hiding in plain sight? Or is Jane a brilliant, broken woman spiraling into confirmation bias? Hartwell’s direction maintains that duality without tipping the scales.

It’s a gutsy choice, and the play is stronger for it. Tying up the truth with a bow would render Job inert. The ambiguity is the point: in a world of weaponized narratives online, who gets to decide what’s real? The audience.

Job is not for the faint of heart. It’s dark, adult and drenched in the stress of content moderation, moral ambiguity, and human suffering. However, for audiences willing to confront something thorny and thought-provoking, this is Curious Theatre’s best offering of its 28th season thus far.

If you’re looking for a show that leaves your pulse racing and your mind grinding long after the lights come up, Job more than earns its paycheck.

A Colorado-based arts reporter originally from Mineola, Texas, who writes about the changing world of theater and culture, with a focus on the financial realities of art production, emerging forms and arts leadership. He’s the Managing Editor of Bucket List Community Cafe, a contributor to Denver Westword and Estes Valley Voice, resident storyteller for the Bonfils-Stanton Foundation and co-host of the OnStage Colorado Podcast. He holds an MBA and an MA in Theatre & Performance Studies from CU Boulder, and his reporting and reviews combine business and artistic expertise.

Leave A Comment