Local Theater Company’s bold staging blends poetry, gospel music and treadmills in a boundary-pushing, mythical journey that’s equal parts disorienting and unforgettable.

When I first encountered Kori Alston’s A Case for Black Girls Setting Central Park on Fire at Local Theater Company’s October 2023 Pop-Up Lab at the Dairy Arts Center in Boulder, I left uncertain.

The piece, read aloud with minimal movement, struck me as heady, fragmented and difficult to grasp. While I admired the piece’s poetry, I struggled to imagine how it could fully live onstage.

Two years later, in the Carsen Theater at the Dairy, that uncertainty melted into awe. Under the direction of Local co-artistic director Betty Hart, the world premiere of A Case for Black Girls transforms Alston’s language into a physical, urgent theatrical journey.

Hart has shaped a 75-minute marathon of relentless motion that fuses spoken word, gospel hymns and powerful performances into an ambitious and, at times, overwhelming but deeply resonant new work.

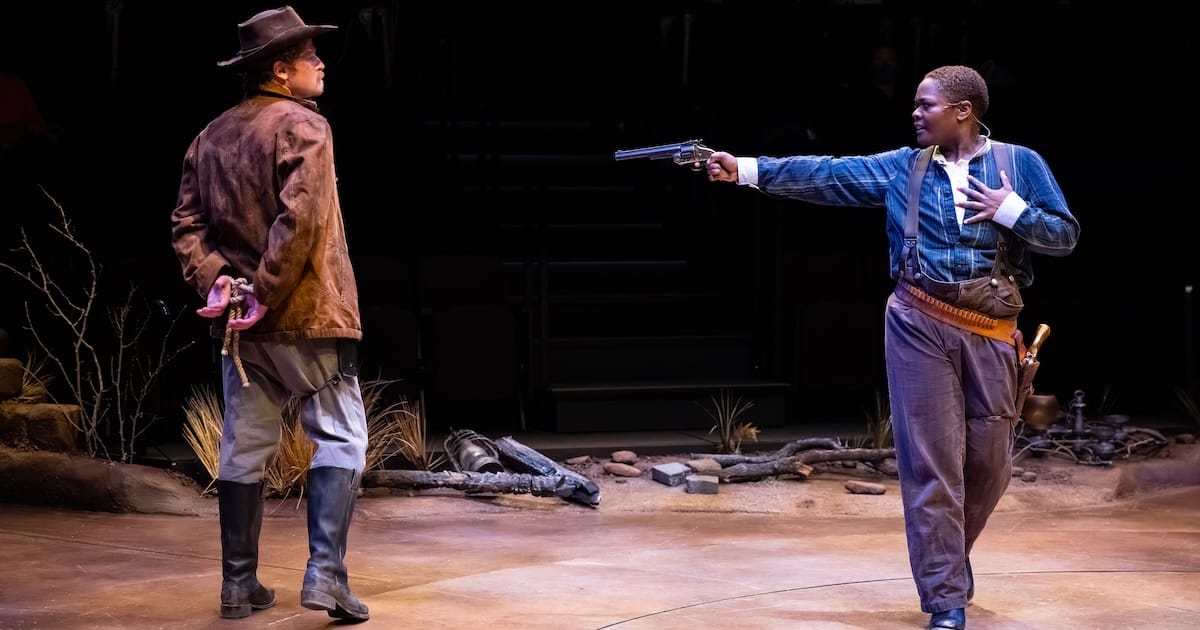

Michaela Murray and Jahalia Coleman. | Photo: Graeme Schulz

A myth for our time

Alston began writing the piece in 2018, when he was teaching seventh grade and listening to the stories of the Black girls in his classroom. From those voices grew “12,” the brilliant, exhausted girl at the center of the play, embodied with ferocious commitment by Jahalia Coleman.

Over one dusk-to-dawn journey, 12 runs from Brooklyn to Harlem with the support of her Rottweiler (Michaela Murray), the ghost of Nat Turner (Dwayne Carrington) and a fire-wielding oracle (Sheryl McCallum). The journey feels like a mix of The Wizard of Oz and Waiting for Godot, as the story charts a fractured but deeply poetic meditation on what it means to carry trauma, history and Black girlhood in one’s body.

As Alston shared in a YouTube video, the play has evolved quite a bit since the Fall 2023 reading and now “has new music. It’s got some new rhythms. It’s got a new ending, but it still has the same core — it still has, I think, that spark that Nick (Chase, LTC’s co-artistic director) and the Local team saw in it in the first place. I feel grateful that they helped me to turn that spark into what I believe is a flame.”

That flame burns bright in Boulder, where Hart’s production harnesses every technical element to match the urgency of Alston’s vision. What once seemed unstageable now unfolds with kinetic clarity, driven by bold design choices and relentless momentum.

Sheryl McCallum in ‘A Case for Black Girls Setting Central Park on Fire.’ | Photo: Graeme Schulz

Staging that never stops moving

From the moment audiences enter the Carsen Theater, the production makes its technical ambitions clear.

Scenic designer Klara Zieglerova has reoriented the space into a thrust, with treadmills embedded in the stage floor, which is painted as a highway, and five vertical projection screens looming like city towers. Before the action begins, facts about Nat Turner’s life appear on the screens and the ground, anchoring the evening in a history of rebellion and survival.

The play starts with a gospel choir lifting their voices in “I’m Not Tired Yet.” Under the music direction of Johnny Nichols Jr., with accompaniment by Dr. Michael Williams, the cast sing a rousing declaration of resilience that collides with the sight of Coleman’s 12, looking utterly exhausted.

Coleman’s opening monologue, a torrent of fear and frustration about living in her Black body, sets the tone. She believes she has heard a call from God to run. But whether she is running toward something, away from something or simply running for survival becomes the play’s central question.

Though 12 is not quite sure why, she soon takes off running and rarely stops. Ingeniously, the production incorporates treadmills built into the stage. With lighting by Emily Maddox that isolates the treadmills with squares of light when in motion, sound design by Alex Billman that recreates the city’s never-ending noise and projection design by Topher Blair that features an animated cityscape that literally moves with the performer, these sequences are startlingly alive.

Flashing streetlights sweep over the performers as they move while city noises, like sirens, footsteps and snippets of birdsong, immerse the audience in a restless New York night. The physicality of the production makes the audience feel the weight of a body constantly in motion, denied rest.

Companions on the road

The play unfolds in five distinct chapters. Following the first movement, in which 12 decides to run, she is joined by Nat Turner, played with warmth and gravitas by veteran Colorado actor Dwayne Carrington. Their historical conversations have a Beckett-like absurdity to them, as they are philosophical, repetitive and funny in their tangents while remaining urgent in their stakes.

In the third section, McCallum as the Alley Fire Woman crackles onto the scene with charismatic warmth and humor. She teaches 12 to master fire, coaxing her toward openness after trauma has made her closed-off and fearful. The interplay of suspicion and generosity in this section is one of the production’s most emotionally accessible passages, buoyed by McCallum’s comic timing.

Equally striking is Murray as the Rottweiler. At times on all fours, at times spitting slam poetry into a microphone, Murray blurs the line between loyal companion and the voice of 12’s own anxieties.

Murray’s slam-poetry-inspired monologue during the fourth sequence about Central Park and the Amazon burning, Wall Street’s corruption and 12’s absent father as 12 runs for her life on all the treadmills onstage is dizzying in its scope. It’s overwhelming by design, a cacophony of personal and political grief that leaves both audience and protagonist panting for breath.

Finally, 12 arrives at her aunt and grandfather’s home in Harlem. In a Wizard of Oz-style reveal, the characters she met along the way return as family members, grounding her odyssey in community, before McCallum sings a gospel-infused finale that reminds 12 of the importance of home and survival.

By the end, the journey has reframed 12’s trauma, rather than erased it entirely. 12 realizes that there is the possibility of carrying pain forward without being consumed by it through leaning on those around her. Though the conclusion is somewhat simplistic given the previous scenes’ highly cerebral stakes, the earnestness of the language and performances sells the moment.

Technical brilliance

There is much to admire in Hart’s direction. The production’s technical components — moving treadmills, synchronized projections, evocative soundscapes — could easily become gimmicky. Instead, they deepen the story’s central metaphor: constant forward motion and the exhaustion of survival.

Coleman, making a standout debut, carries the evening with remarkable stamina. Her emotional range, which shifts frequently from fury to vulnerability to confusion to cautious optimism, grounds the production even in its more abstract moments. When Coleman collapses onstage during the fourth movement, gasping that she cannot keep running, the audience feels every mile with her.

That said, A Case for Black Girls will not be for everyone. If you crave a neat story arc or escapist entertainment, this won’t be your show. Its structure demands constant attention, its language is often highly poetic and its shifts between myth, history and contemporary politics can feel disorienting. However, if you’re open to experimental work, the rewards are rich.

When I first heard A Case for Black Girls read aloud in 2023, I wasn’t sure it could stand on its feet. Seeing it now, I realize it was always meant to be in motion. Hart and her team have turned Alston’s fragmented poetry into a living, breathing performance that demands stamina from performers and audience alike.

It’s not tidy, it’s not easy and it certainly won’t be for everyone. But like the myths that endure, its power comes from the way it lodges in the body and mind long after the lights go down.

A Colorado-based arts reporter originally from Mineola, Texas, who writes about the changing world of theater and culture, with a focus on the financial realities of art production, emerging forms and arts leadership. He’s the Managing Editor of Bucket List Community Cafe, a contributor to Denver Westword and Estes Valley Voice, resident storyteller for the Bonfils-Stanton Foundation and co-host of the OnStage Colorado Podcast. He holds an MBA and an MA in Theatre & Performance Studies from CU Boulder, and his reporting and reviews combine business and artistic expertise.

Love this full and detailed review. It was written with care and precision.

I felt it all the way in Los Angeles and only regrettedafter reading not being able to witness this piece in the flesh.